Rosemary LoganCheckout the Spring 2020 section of NAU's two-semester Permaculture Design Course Blog! Archives

December 2023

Categories |

Back to Blog

Simple Living in Cascabel3/9/2020 By Sierra Riker  Cascabel is a small settlement just northeast of Tucson, Arizona. Many of the residents had built their homes and live sustainably on the land. Despite the neighbors being so far apart, they share a tight-knit community through community dinners, common areas, and a community garden. David Omick and Pearl Mast in particular have an abundance of knowledge in living off of the land. They hand pump their water from the water table, use a solar heater for showering, and store their food in barrels outside and refrigerated goods in an ice chest that they leave open overnight and close during the day. David and Pearl also have a garden with a net over it to keep wildlife away, a solar oven for baking, and a solar array. They use the compost from their composting toilet to supply the garden. David and Pearl play a large role in helping the community with the community garden, building solar arrays for their neighbors, and other projects like building cairns for the local trail system. See omick.net for more information and guides. Above: Cascabel community garden Below left: David and Pearl's solar oven Below right: David and Pearl's personal garden

How to Build a Cairn: 1) Find an optimal location- Cairns are generally used to mark trails when they are not visible over a distance, so building one next to the trail and on a higher part of the landscape is recommended. 2) Gather stones appropriate for the size of the cairn- Depending on the height, larger rocks are needed for taller cairns and smaller rocks are needed for shorter cairns. It is important to find an assemblage of shapes. Flat rocks work well for the edges while round ones fit in the center. 3) Lay a base ring of rocks- Make it wide enough to support the height of the cone. Many rocks have a slant to them, so make sure the slant is facing the center of the cairn to improve stability. 4) Stack the rocks- Continue to stack the outer edge in rings while keeping the center and edge level. Make sure the rocks are stable and the walls slope gently inward. 5) Put a centerpiece on top- If you find a unique rock, place it on the top! It helps to make the cairn more eye-catching and adds a bit more fun into building it. Congratulations! You have built a cairn. It should be stable enough to remain standing, requires little up-keep and will be beneficial to all hikers using the trail. Above: One of the completed cairns in Cascabel.

0 Comments

Read More

Back to Blog

The day started out rainy, but soon it got started as we all dried our gear and took shelter inside to watch earthen videos. Benito shared videos that he and his brother had created, which were truly captivating, from their youtube channel called The Nito Project. Their artfully crafted home was a joy to be in, and a wonderful example of their families work. Athena showed off her son's Japanese Clay Balls, which is polished clay and comes in many different styles. We also got the opportunity to watch a video of Athena doing a piece of earthen artwork on one of their dwellings, featured in the video below. Soon half of our crew had to head out while the other half of us stayed to eat lunch. After our bellies were full and the rain clouds had parted, we took a trip outside to do an earthen workshop with Bill. Bill showed us his studio, which had many different earthen canvases where others had practiced in previous workshops. He then took us to his dwelling, where he kept all of his pigments and materials for mixing. We also talked briefly about how important it is to have a relationship with these living buildings. Bill explained that sand and straw prevent cracking, giving the dwelling structure and body, whereas the clay is like glue. For mixing paint, he told us the ratio of sand to clay should be 1 part sand and two parts clay. He made the analogy that mixing can be much like making pie, as you have to add water carefully to get the ratios right. Depending on how thick or thin you make the mixture, you will get different levels of paint opacity. If you would prefer the paint to be water-resistant, you must add glue. Additionally, you can add mica for some sparkle!!! A good source of clay for this kind of project in Phoenix, as recommended by Rosemary, is Marjon Ceramics. Bill also mentioned Bioshield Clay Paints is a good source for paint materials. Bill then joked that mixing and building were two different trades. "Sometimes, the person who can put it on the wall is not the most adept at mixing it." After the workshop with Bill, we packed up our gear after thanking them for our time and drove to Cascabel. First, we got to visit an earthen home recently built that had a lovely screened porch. There was also a hay bale shed that worked well as produce storage. Once inside the house, we got to see the kitchen and the living room. In the living room was a charming wood-burning stove with beautiful green tiles. We then walked the stairs up to the loft and entered onto the balcony through a cute window. The view from the balcony was stunning, and the spiral staircase was so sweet and whimsical. By the woman's desk, we also got to see glass colored bottles used as windows through the earthen walls. We thanked the owner for her time and continued down the road to another kind ladies' house. This house was smaller and completely earthen. There were orange poppies everywhere. The shape of the earthen home was truly beautiful, and we all gawked at how wonderful and rewarding a life of simplicity can be. Her bathrooms and kitchen were outdoors. She allowed us all to go into the small structure and enjoy some shade and beautiful design. Afterward, we moved on to another home, although this one was not earthen as much as it was stone. The house was thoughtfully built with a loft for sleeping and a living space/miniature kitchen downstairs. Once we finished touring all these lovely homes, we went to the Cascabel Community Garden to et up camp. We unloaded breakfast food from Rosemary’s truck and set up camp. We said goodbye to Rosemary and played around until dinner. At dinner, we had a fun Fritos taco salad dish and celebrated having our wonderful mentor, Rosemary. We also got to know some of the community members better and got to socialize with each other at the Cascabel Community Center. Once dinner was over, we cleaned the kitchen and drove back to the campsite. The moon was full, and the Saguaros casted moonlight shadows all over the landscape. Andrew made a fire that we all shared and enjoyed. One by one, we all drifted to sleep. What a wonderful day!

Back to Blog

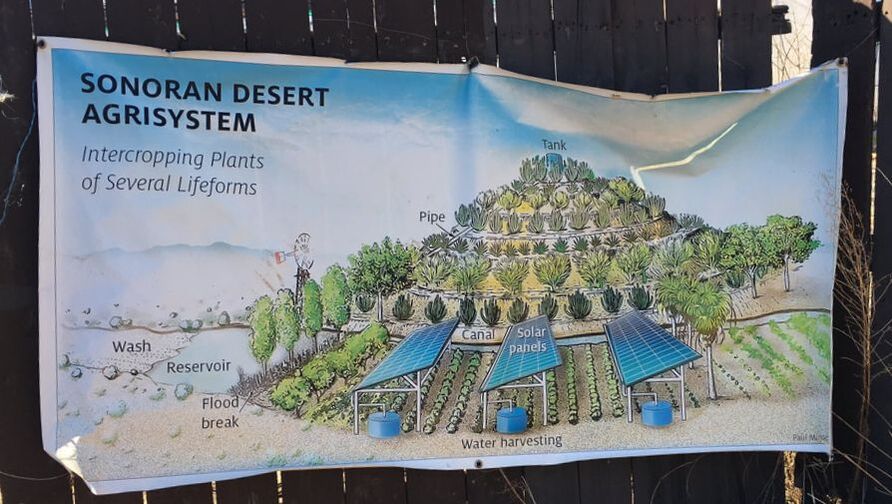

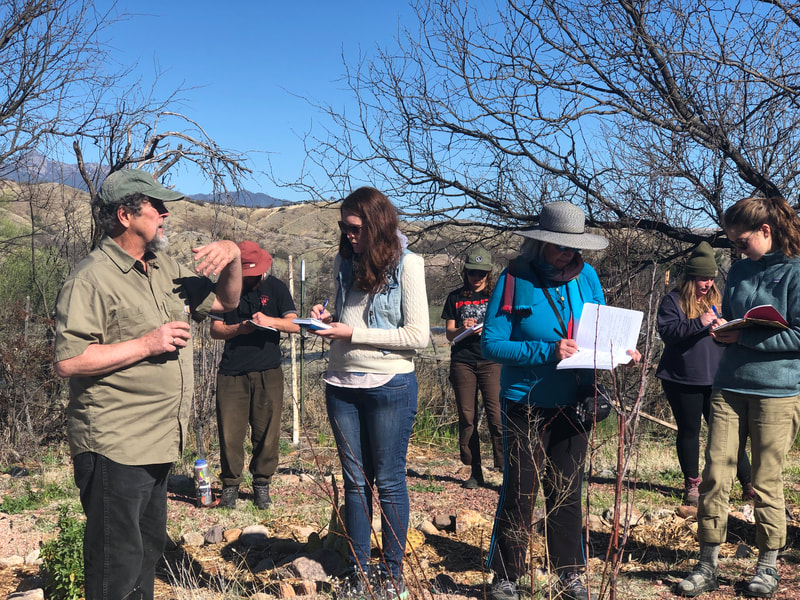

by Kira Farmer and Shaelyn Lau Our permaculture class had the privilege of being invited onto Gary Nabhan’s property in Patagonia, Arizona where he focuses on implementing dryland farming principles on arid lands in a time of water scarcity and drought, energy use transition, and accelerated climate change.

To further support this belief, Nabhan provided us with seven tips that he deemed essential in creating an agrisystem in the Sonoran Desert:

One of the biggest take-aways we got from Gary refers to tip number 4, where we talked about agrivoltaic systems, in which you can grow food under solar panels on stilts. This allows energy generation for greenhouse production and other power-necessitated activities while creating micro-environments underneath and around that are buffered from high heat, freezes, hails, etc. They also embody permaculture principles in that they also work with their human counterparts, providing shade for relief from heat exhaustion that many farm workers experience when harvesting in arid landscapes. What is amazing about agrivoltaic systems is that a space has now been transformed from only one type of generation to the generation of energy and food in the same space! Water was a big topic when talking about producing food in Aridamerica. We talked of the exponential growth in energy costs as we dig deeper down per foot to pump water. We talked about the risk of the salinization of soils as the groundwater gets tapped out without time to recharge. When it comes to experimenting with creative and innovative means of producing food in hotter, dryer landscapes, permaculture principles will serve as a baseline for restructuring the way we grow food as designs shift to meet our environment in the state they are in. For most places, this will include less abundance of water. The biggest shift, Nabhan talked of, was the necessary change in mindset for farmers. How restructuring what you grow, when and how you grow it, and the scale at which you grow will be essential. Farmers should be looking to native crops in their region and prioritize perennials in order to increase the stability of their landscapes, working with nature instead of against it. This tied to the growing labor and research he was conducting when we visited him. He talked of the power of agave and mesquite. Two native plants to the Sonoran Desert. Agave and mesquite when companion planted have the capacity to draw massive amounts of CO2 from the atmosphere into the ground and produce immense amounts of above and below ground biomass on a year to year basis. They require little to no irrigation to survive as well as thrive, making them almost impervious to rising global temperatures and droughts. Not only are they important for regenerating the landscape, but agave is found to be nutritious as a food product with probiotic elements rather than simple sugars. Agave when used with permaculture principles (not being turned into syrups or tequila) can help to combat diabetes rather than cause it because all the nutrients and carbohydrates are not cooked away. As we navigate a shifting world and a climate that will force us to adapt to drier and hotter landscapes, both in the food we produce and in our communities of humans, it is important to begin to re-vision who we are and how we are a part of this world. Gary Nabhan introduced us to his use of the word holobiomes. We should no longer consider ourselves as human beings. Moving away from our Western notion of being separate from or dominant over the natural world but of it. We are holobiomes just as soil is a microbiome. Holo meaning whole, entire, complete. We would like to extend our utmost gratitude to Gary Nabhan and his wife, Lori, for hosting us and sharing their wealth of knowledge. We can't wait to implement these tools into our own lives.

Back to Blog

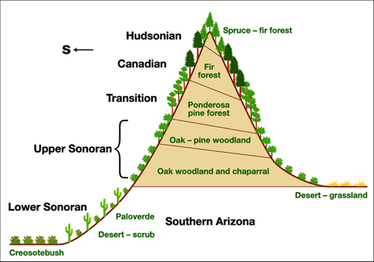

Day one of the Tucson/Canelo permaculture field trip consisted of visiting Native Seeds Search and Avalon Ecovillage. While these settings provided critical insight, I found the physical journey to arrive in Tucson was of similar importance. Heading south of Flagstaff, our caravan descended the Mogollon rim. As the road spiraled downwards in elevation, I noticed several amendments in temperature, moisture, and vegetation. Temperature levels and spring budding in vegetation became more prevalent the lower we went. Between the initial 7,000 feet to 6,000 feet, the seasonal cold and frozen snow slowed the growth of the Ponderosa Pine. I saw limited understory and no signs of spring blooms. Between 6,000 feet and 3,500 feet, I noticed a shift: –snow coverage was sparse and less dormant vegetation became present. Scrub Oak, Pinon Pine, Juniper and Manzanita thrived the lower we went. As we approached Tucson, I noticed the largest shift in temperature and vegetation. Between 3,500 feet and the valley floor, the signs of spring became present; Mesquite, Palo Verde, Agave, Yucca, Barrel cactus, Saguaro, Cholla were all beginning to thrive. I even noticed the California poppy and Desert Lupine flowering. Although this descent may seem obsolete to many, I learned that elevation is a critical factor that affects temperature and moisture. Both of which affect plant growth. Hence, when looking to garden at any elevation, one should review the gradient changes. Once our caravan stropped in Tucson, I happily shed my strange layers to prance around in a t-shirt. Here, we visited the Native Seeds Search: https://www.nativeseeds.org/ Our tour guide Hannah discussed the importance of conserving agricultural biodiversity through a variety of methods. These included: Open pollination, maintaining native heirlooms, practicing organic growing principles, using no GMO’s, and mitigating the use of seed patents. While these methods were discussed, I realized that a precedent was being set. The Native Seeds Search has found a venue within a capitalistic system to incentivize the preservation of native seed types. This preservation has allowed for seeds to be grown and donated to local tribes, families in need, and other organizations that usually do not have this access. While this organization profits monetarily, they conserve native biodiversity. Cultural growing heritage found in this region is continued through the preservation of these endemic seed types. However, the commodification of seeds adds discontent to my heart – since seeds in the past have been dispersed in a less sterile and more harmonious way. I do however understand that in today’s way of business, this module helps push for the greater good – to preserve the native seeds and culture of yesterday and provide for tomorrow's abundance. Directly after visiting Native Seed's Search, our group visited Avalon Eco Village. This organization can be found at https://avalongardens.org/ Avalon is a spiritual eco-village with 120 on-campus residents located outside of Tucson, Arizona. Avalon’s 200-acre property is cared for through permaculture principles and design. The beauty of earthen material homes, orchards, and wetlands make for an oasis in the hot Sonoran Desert. As soon as our crew entered the property, our permaculture whirlwind began; we were but mear tumbleweeds in what was to come next. Avolon water’s the entire property's agricultural system (3 greenhouses, aquaponics, multi-acre orchard, and agricultural fields) through the rain-water catchment. Buried below ground, specifically under fruit trees and around dwellings, are water infiltration tunnels that capture rainwater and greywater, and slowly disperse to the fruiting trees and lawns. This system, in the permaculture way, is an intensive set-up, but passive once going requiring very minimal input. The rainwater catchment system on the dwellings is channeled off the gutters with a first-flush system that diverts clean water into a cistern and muck water onto the nearby flora. The water catchment capacity for the entire property is 2.5 million gallons. Avalon’s drinking water is sourced from an on-property well, making its entire water system self-sufficient. Avalon treats most of its waste through an onsite treatment. The waste is gravity fed from the main housing into a three-tank system. The first two tanks filter the waste and the third tank adds Effective Microorganisms (EM). This mixture of EM and filtered waste is then pumped underground through lined underground tubing into an artificial wetland. This artificial wetland is a migratory stopover for many insects, birds, and mammals. The waste treatment is up to the Tucson city code. The waste from other onsite facilities is pumped into a septic tank. The community has been cultivating an orchard and several agricultural fields for the past 10 years. Currently, 30% of the community’s diet is sourced from the property. They cultivate a combination of food crops, cash crops, and horticultural crops. They recently worked with Native Seed SEARCH to bring back an Indigenous grain, local to the region, which they seed-save as well as mill into flour. Avalon also has a growing food forest on the property, where members collect the fresh fruit and chicken and pigs collect the fallen fruit. Avalon’s water catchment capacity is epic in scale. The community shared lots of wisdom on how to start small or go all the way. The permaculture principles and design of the property are inspiring for how to scale-up many examples we have learned about. About the author This entry was jointly written by Molly Carney and Andrew Volz. Both students have an affinity for bioregional food and riparian ecosystem conservation. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed