Rosemary LoganCheckout the Spring 2020 section of NAU's two-semester Permaculture Design Course Blog! Archives

December 2023

Categories |

Back to Blog

McKenna Bean & Mariessa FowlerGraduate and Junior undergraduate According to the Navajo language, Ch'ishie means "dirty or ashy." This is a perfect name to give a farm that grows food in the desert landscape of the Navajo Nation in northern Arizona. This Friday, the permaculture class had an opportunity to escape the late September chill in Flagstaff and ventured east to Ch'ishie Farms. We arrived at Tyrone's home, which was built with permaculture design in mind, and explored his property, which offered chickens, sheep, hoop houses, and a geodesic dome. The space also serves as a growing space for seed starts, as Tyrone grows about 40,000 seedlings yearly. He showed us his different hoop house models and described the pros and cons of different types of shade cloth and how they facilitate growth throughout harsh conditions. One of his hoop houses uses plastic and shade cloth to insulate the space and allow for a longer growing season, allowing his tomato plants to grow well into November. This hoop house also serves as a windbreak for the rest of the property, as the plastic-reinforced structure does not let wind permeate it. The other hoop house on Tyrone's property incorporates a different shade cloth, allowing outside air to get in through the fabric's holes. This space has fruit trees and premature plant starts and is connected to a geodesic dome. Tyrone is in the process of retrofitting the roof of his home to harvest rainwater to hydrate his at-home garden, which is crucial in this case as everything is hand-watered and this property is off-grid. Finally, we ventured into the garden, where Tyrone and his family built beds made of cinderblocks and other materials. After the tour of his family home, we piled into our vehicles and made the trek down a dirt road to Ch'ishie Farm.

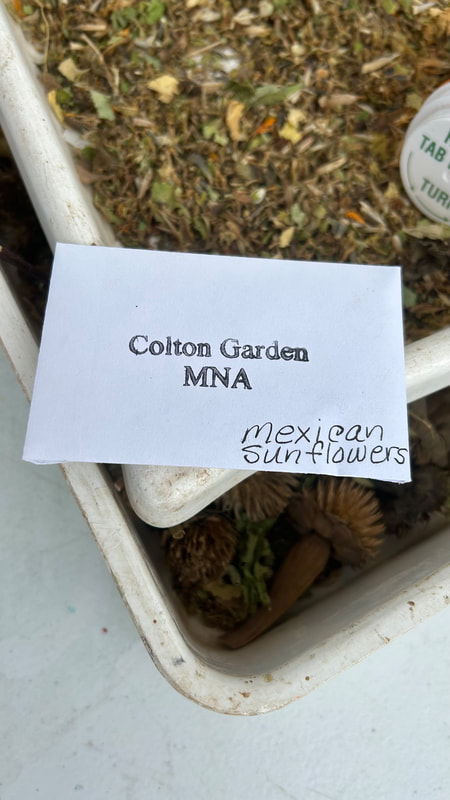

Tyrone's community field is based 11 miles away from his family home. The field runs alongside the Little Colorado River, a lifeline for the Leupp community. Tyrone began this portion of the trip by describing a recent flood that affected this land. It affected infrastructure and some of their equipment was damaged. Every once in a while, the Little Colorado River will flood, submerging the Ch'ishie farm in feet of water. After taking it all in, we began helping Tyrone by picking up and tidying the drip irrigation lines and harvesting corn and squash. We harvested many tubs and wheelbarrows full of corn and squash to be sold at the upcoming Indigenous market held at the Colton Garden, almost filling up the bed of Tyrone's truck! The squash grew massive and it was exciting to weave through the vines for these surprises. Eventually, it was time to head back to Flagstaff and reflect on what we had learned that morning. The dramatic landscape where the desert meets the Little Colorado River mixed with the Lush fields of corn and squash was awe-inspiring and reminded us how resilient agriculture can be. Tyrone is a steward of traditional knowledge and a leader in the local food sovereignty movement. We are so grateful to have had the opportunity to learn from such an influential teacher. Tyrone does a great deal to help his community and during the pandemic, he was able to garner funding to build hoop houses. This encouraged many community members to practice food sovereignty. He mentioned how several other community members utilize the fields during the growing season and grow their intergenerational squash and corn varieties. Many of these farmers also practice dry farming techniques because of the dry and arid environment in the Leupp area. Tyrone also funded a project for solar pumping groundwater for the field and possible future freshwater resources for Leupp. The water was stored on top of a hill and many residents often harvest the water for agricultural or livestock purposes.

0 Comments

Read More

Back to Blog

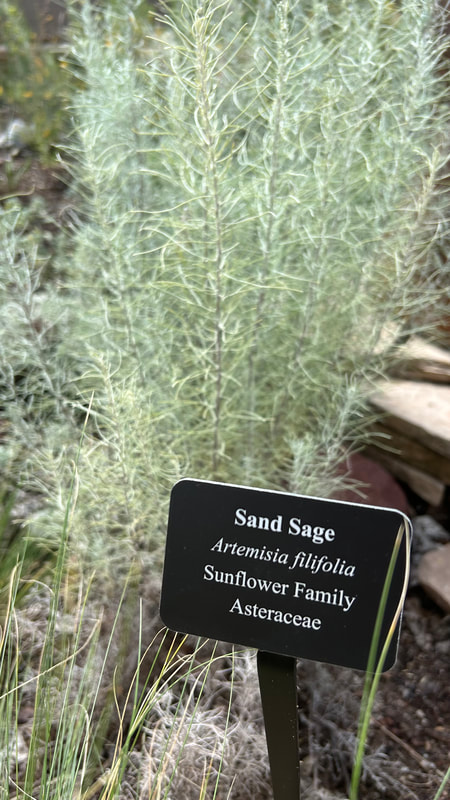

Ben Steller & Mariessa FowlerPermaculture students At the beginning of this field trip, we met with Phyllis Hogan at the Michael Moore Medicinal Garden to talk about medicinal plants and ethnobotany in the Southwest. Phyllis Hogan is a longtime ethnobotanist in the four corners region. In 1976, she created her store in Flagstaff, Arizona, called Winter Sun Trading Co. This local store specializes in the selling of herbal medicinal and local Indigenous art. Then, in 1983, she co-founded the Arizona Ethnobotanical Research Association. This vaulted her into ethnobotanical prominence in the four corners region, and she has been positively contributing to this region ever since. To begin her talk, Phyllis introduced us first to her and her backstory, and then to her methods of honorably and holistically harvesting plants. As she described it, harvesting plants is a privilege and must not be taken lightly. She described how first, one must burn juniper as a method of connecting with plants and connecting with our ancestors. Then she described how we should make a prayer offering to the plant and to the sun. In this prayer offering, she instructed us to tell the plant who we are, and that we should ask for permission to pick it. If it gives us permission, then take responsibility and never overharvest. And if it does not give us permission, she instructed us to never violate that expression from the plant. Only if you go through all of these steps and receive appropriate permission from the plant can you then harvest. For this field trip, we met at the Michael Moore Medicinal Garden. This garden is located on the property of the Museum of Northern Arizona, and it was formerly a parking lot. Now, it is an herbal medicinal garden named after another renowned ethnobotanist of the region, Mr. Michael Moore. This medicinal garden, named after him, is filled to the brim with beautiful medicinal herbs with all sorts of uses. Phyllis showed us examples of some of these herbs from her own collection, among them being the osha root and the yucca root liquid. Both of these have medicinal uses as anti-inflammatory plants. In the garden, we saw lots of sage and various types of medicinal flowers. After touring this garden, we headed up to the Colton Community Garden. The Colton Garden was located right behind the Michael Moore garden and is a communal garden site for the community of Flagstaff. We met with one of the main people who manages the garden, her name is Fitz. She first went over seed saving and how it differs by region. Also how important seeds are because they have genetics and store information. Moreover how you need seeds in order to grow things. For certain seeds, the method of seed saving is different because tomatoes and cucumbers are wet, they require water to germinate. It creates mold which then breaks down the wet layer and you are left with dry seeds. For dry seeds, the process is also different. Community building and sharing is experienced through seed saving. People share their seeds with their neighbors and it usually is for plants that best suit their climate. Then Fitz discussed their favorite vegetable, beans! There are so many varieties of beans especially in this region. Beans grow really well in the Flagstaff region and are beneficial to the soil due to its nitrogen properties. Also they are really good for storing in the winter time and you just need to save a certain percentage for the upcoming growing season. After this demonstration of seed saving and beans overview, we explored the garden. There were a variety of displays for different gardening techniques like keyhole gardening, community composting, sheet mulching, zuni waffle layout, hoop houses, arch trellis for squash, passive solar greenhouses, intercropping, three sisters method, permaculture, and even an indigenous crops garden for a program with indigenous flagstaff students. The keyhole method is best summarized as a compost bin built into the middle of a raised bed. It gives the garden bed the ability to retain moisture, nourish the soil, and improve productivity. The Zuni waffle design is when garden beds are sunken in squares covered with clay or soil walls that keeps water enclosed in these circles. They are efficient in conserving water and improving moisture. The Colton Garden also has a space for children and there is a separate area for children to play. It's behind some willows and connected by a tunnel. There are different books and activities left there for children to interact with while they are there. The kids learn how to plant and harvest. They are currently in the process of creating a geodome for the children to do more planting and growing opportunities. The Colton Garden is very community oriented and actually hosts a lot of events involving the community like workshops and farmer markets. They are open for compost and food scrap collection. But the garden is very inclusive and we can definitely learn from them!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed