Rosemary LoganCheckout the Spring 2020 section of NAU's two-semester Permaculture Design Course Blog! Archives

December 2023

Categories |

Back to Blog

Marigolds in Permaculture12/7/2023

Ultimately Marigolds serve a wide variety of purposes which is valuable in a permaculture mindset when choosing plants that can serve multiple purposes and benefit your space in several ways Blog Post By: Gabriel Navarro, and Emma Dveirin for ENV499

0 Comments

Read More

Back to Blog

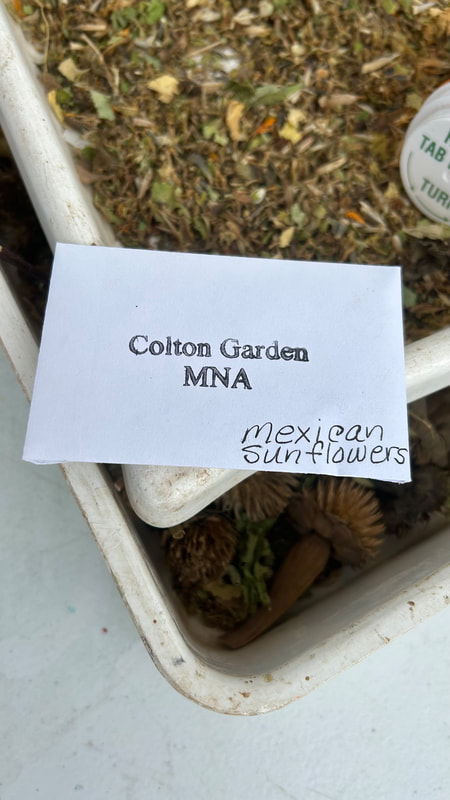

Successful Growing in Arid Flagstaff12/7/2023 Northern Arizona poses a difficult environment for many growers to adjust to. We live at a high elevation with an arid ecosystem that has high chances of frost and extreme temperature change. So, it's no easy feat growing an abundant yield in this environment. This semester, we were able to see successful growers in Flagstaff and learn about their adaptive techniques for this harsh environment. Most notably, the Museum of Northern Arizona’s Colton Garden, provides a beautiful example of the potential of growing in cold and arid conditions. Here we observed many different growing methods, including permaculture techniques such as herb spirals, key-hole beds, mulching, and static composting. Colton garden exists on a larger scale though, compared to a new grower in Flagstaff with solely their backyard. Fritz, the resident gardener for Colton, uses her experienced knowledge to keep the garden thriving and mentor rotating interns who help maintain the garden. In the middle of the semester, we were able to meet two independent permaculturists, Greg and Patrick, who had some of the most highly productive and successful gardens we’ve seen in Flagstaff. From multiple composting techniques, to luscious greenery growing through winter. Greg even had strawberries growing in his garden in early November, something we have never witnessed before. Greg was most outwardly passionate, telling us about his varying compost techniques. He prides himself on having nutritious soil, something that can’t be achieved without a continuous flow of organic material. In Greg’s case, his compost. He had kitchen compost that was collected in an anaerobic bucket, so that the compost wouldn’t rot and stay warm before its use. He also had stack composting where he would layer different types of organic material, starting with wood chips, then food scraps, then coffee grounds, then whatever other material he could find such as hay and he would restart once the pile was low. This created a healthy aerated compost that he would then use as soil for his plants. He would sometimes use vermicomposting with this stacking compost. He would add worms such as red wigglers to break down the material, and attract other worms and small wildlife to continue this decomposition process. He would also inoculate his soil with mycelium to improve plant health as well as soil health. All of this work was to keep the soil productive and healthy during cold winter months so that the plants have a better chance of survival. Greg’s colorful and energetic personality made the afternoon more lively. Patrick and Greg could not have been more different with how they employed their permaculture techniques. While Greg utilized a more “free” and “wild” garden, with plants and pots strung throughout the yard with some, but little, strategic thought, Patrick placed his plants intricately (picture on right). Beds in the front yard included species that need additional sunlight and attention. The backyard held most other crops, some needing daily tending, but not all. His hoop house and small greenhouse were organized by plant species; Peppers with peppers, flowers with flowers, leafy greens all in one section. His knowledge and organization level was extensive. Patrick saves his seeds and keeps a collection of community-sourced native seeds. He writes and sends out an annual newsletter to other prospective gardeners. These are just a few examples of the lengths Patrick goes to in order to share his valuable ecological knowledge. The opportunity to see and explore some of the successful gardens in Flagstaff, Arizona provided valuable insight into overcoming the challenges of gardening in an arid, high-altitude environment. The Museum of Northern Arizona`s Colton Garden serves as a prominent example of permaculture in modern society by utilizing techniques such as mulching and static composting in large-scale community gardens, through the expert guidance of resident gardener Fritz. When meeting with independent permaculturists like Greg and Patrick, we were able to see the diverse and inspiring approaches to successful backyard gardening in Flagstaff’s environment. Greg's commitment to nutrient-rich soil, enhanced through his composting techniques, emphasized the essential maintenance of soil productivity during harsh winter conditions. In contrast, Patrick's permaculture strategy, which has much more meticulous organization and strategic plant placement within his garden, shows a high level of knowledge of companion planting. Along with this is his continued seed preservation and community engagement. The visual examples provided by Greg and Patrick's gardens, which captured flourishing plants and advanced cultivation practices throughout the warm and into the cold season, now serve as references for future gardening endeavors in Flagstaff’s demanding climate. All together, these gardens show us the importance of adaptability, knowledge-sharing, and creative problem-solving in cultivating thriving gardens amidst the arid and demanding conditions of Flagstaff. Mackenzie Schutte, Emma Dorch, Mallory Decker Permaculture: ENV/SUS 499

Back to Blog

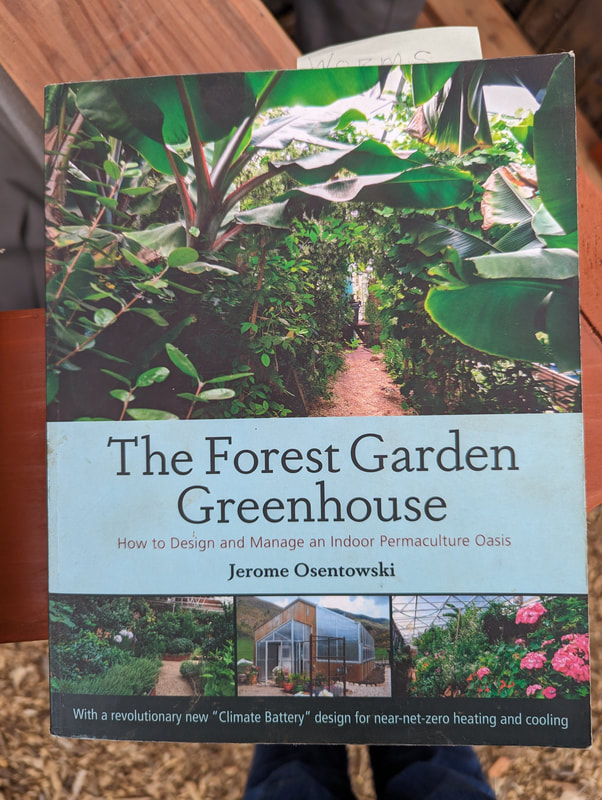

Colton Garden: An Exploration of Soils11/30/2023 Emily Roll On November 15th, the permaculture class went to Colton Community Garden to experience a workshop on soils with Fritz. We worked on building up garden beds for a youth greenhouse in a geodome design, and laid down pathways in one of the larger greenhouses with red wigglers and compost to create a nutrient-rich soil at the base of the garden beds. We had access to many different types of organic materials to build up healthy soil and begin the process of nutrient cycling to prepare for growing next season. The knowledge gained from this trip was unmatched, and we were given many resources on soil and food growing that are shown below.

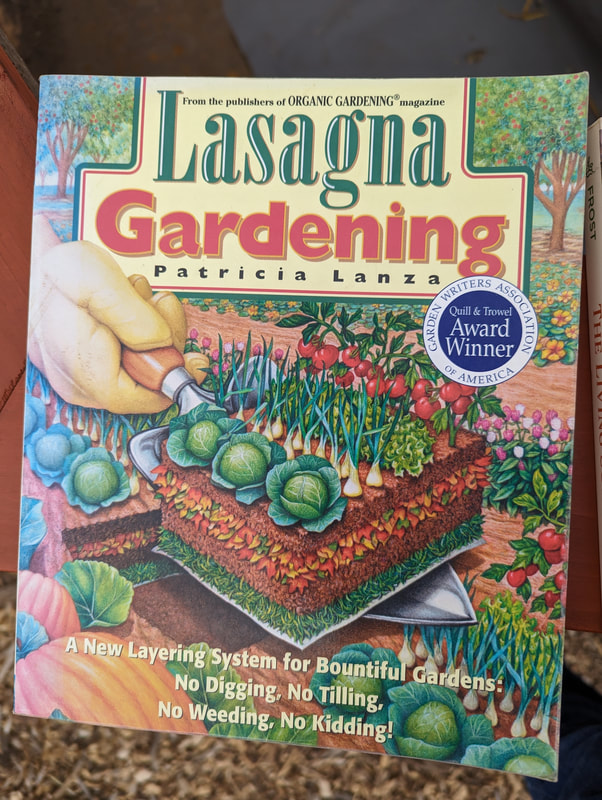

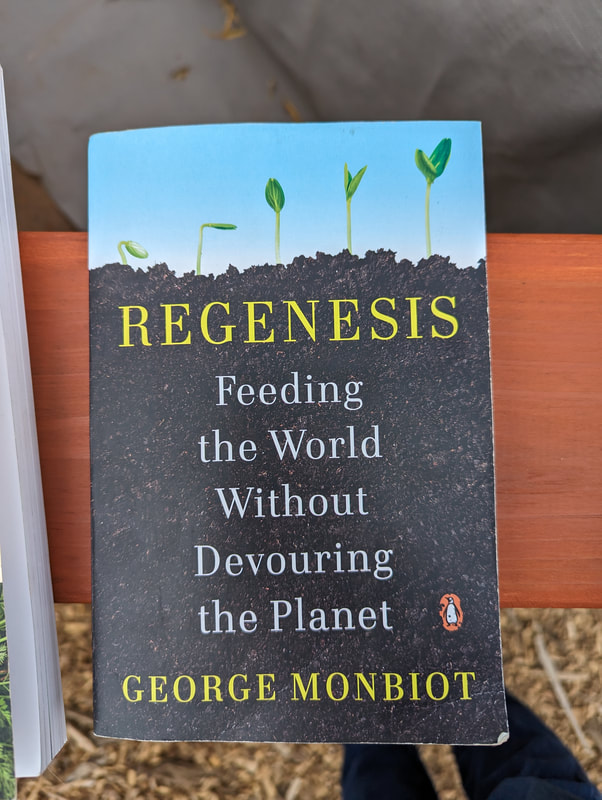

The importance of soil in food production is almost indescribable; soil is the home of nutrients and microorganisms that give our food the nutrients we humans need. Soil acts as an ecosystem, home to worms and microorganisms, nitrogen and carbon, that all come from the layering of organic material and water. As said previously, we were given access to various materials to build up our lasagna gardens as Fritz describes. We had compost from community drop off and the river trip waste that was high in nitrogen. We also had leaves to provide carbon into the system, large logs to add an element of hügelkultur, bigger pieces of dry straw, coffee grounds, and existing soil. All of these things layered together with water will decompose and become the home to microorganisms and mycelium that will work to decompose all the food scraps and larger materials into a mixture of nutrient exchanging. Another aspect of soil building that could be added, that we did not have access to on this visit, is charcoal or biochar. Adding charcoal to garden beds has been a somewhat tricky and recent subject to the world of permaculture and gardening. There is debate on the best time to add charcoal into beds, whether it is activated or inactivated, and the depth to which it should be buried in the soil. The benefits of activated charcoal are becoming clear; it creates areas of nutrient and water retention and microbe habitat, lightens dense soil to allow better root growth, and aerates to increase drainage. Charcoal can also be used in soil that has been damaged by chemicals or pesticides as it brings down acidity and neutralizes the chemicals. The best way to add charcoal to garden beds is simply to just start trying it; every soil system is a bit different and trial and error may be the best way to determine the real impacts of charcoal in especially at-home gardens. Soil is an inexhaustible resource in gardens, and in permaculture as a concept. Soil connects every aspect of the earth together, and gives us the resources we need to thrive. It needs to be taken care of just as it provides for us, and that is truly where permaculture comes into the picture. Perma-culturists believe pesticides are not necessary to having a healthy and protected ecosystem, nature does that on its own and celebrates diversity. Applying these principles to soil gives a head start to letting nature do what it will do in that micro-ecosystem. Encouraging microorganisms and even what we characterize as pests into the garden, letting them all interact will, in most cases, actually helps the soil thrive and in turn our food to thrive. As said earlier, trial and error is a major part of the permaculture system, allowing failures can sometimes turn into the biggest successes. Using resources is also important; doing research into such things as the soil ecosystem will give gardeners the knowledge to really boost their production and bring them closer to their gardens. The resources shown below are ones Fritz was kind enough to share with us, and they are a good place to start in the world of permaculture.

Back to Blog

By Sufyan Suleman

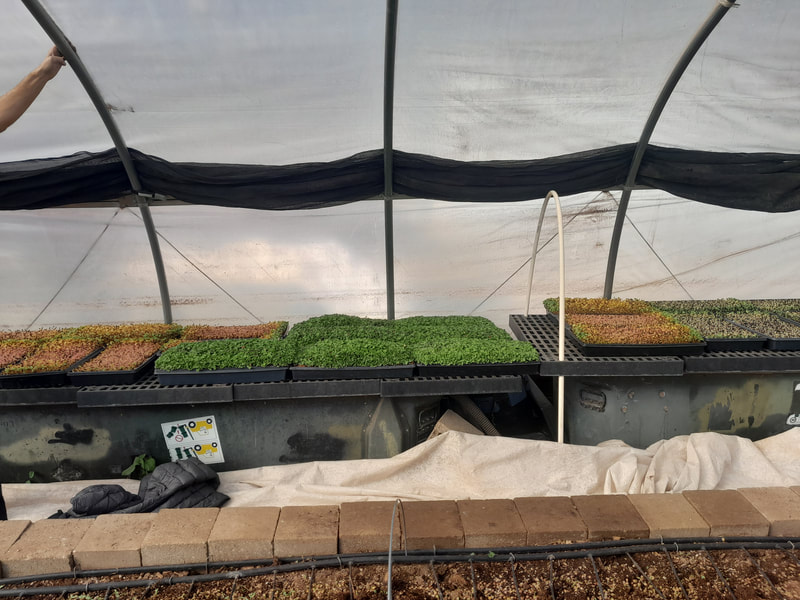

MA Sustainable Communities Northern Arizona University Our visit as a class to Forestdale Farms in Flagstaff on November 7 2013 was nothing short of a revelation. Nestled in the heart of the countryside, this eco-friendly place opened my eyes to a world where sustainable agriculture was practiced. Our exploration of the farm's various facets, from microgreens production to the ingenious zero-waste system, left every one of us in awe of what a harmonious relationship with nature could achieve. The Greenhouses The day commenced with a visit to the hoop house with Rylan as our guide, who is the owner of the farm. The controlled environment allowed for year-round cultivation of a myriad of plants, including radish, peas, cabbage, broccoli, and microgreens. From the careful selection of seeds to the precisely controlled environment, the dedication and precision involved in their cultivation were evident. Growing inside the "tunnel" (greenhouse), as he called it, he explained that not only does it extend the growing season but also limit the amount of intense UV light, which leads to higher productivity, quicker germination, fast maturity, and cleaner and better cuts on plants, especially the greens. When asked about pest attacks, he explained that they do not experience pest problems because they keep their soils healthy, which produces healthy plants that develop defensive mechanisms against pests. These soils are built using compost, irrigation of the plants with water from fish ponds, which brings in nutrients such as nitrate from the fish waste, and finally, from the leftover flats after harvesting the microgreens, which are dense with nutrients. In the microgreens section, plants such as radish are densely planted, which are characterized by a quicker production cycle of 7 days, leading to 100 -200 Ib yields per week. The planting medium for the microgreens is built from the mixture of coconut coir, peat moss, and small amount of compost. Rainwater Harvesting: A Gift from the Skies "We are cautious of our water usage here, and that is a big part of our farm practices and sustainability", said Raylan. The rainwater harvesting system was a testament to the farm's resourcefulness. Collecting and storing rainwater not only ensured a sustainable water source but also minimized the environmental impact of the farm's operations. It was a powerful reminder that every drop of rain could be utilized wisely. Raylan mentioned that the farm is not connected to the city water system. They are solely dependent on rainwater harvesting and hauled water throughout the year. Rainwater is captured and stored in several tanks, streams, and the fish pond. All the farm buildings are designed to capture rainwater, and as a result, the farm stores about 50-60,000 gallons of water a year, according the Raylan. Using rainwater, Raylan explained that previously they used drip irrigation method for the plants. However, according to him, drip irrigation leads to spotty germination, especially when the plants are densely planted. As a result, the farm introduced an overhead irrigation system for the first few weeks, especially for densely planted crops, which leads to even germination. After germination they switch back to drip irrigation, resulting in water conservation as the densely populated plants maintain moisture and prevent water evaporation. The Zero-Waste Loop: A Model for Sustainable Living Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Forestdale Farms was its closed-loop system with zero waste. Every resource was efficiently utilized, and waste was minimized through composting, recycling, and creative repurposing. For example, farm waste after harvesting is fed to the chicken and rabbits, which in turn produce manure for composting and fertilizing the beds. The rabbits are used to clear leftover plants on the beds while fertilizing the soil. Waste water from the fish pond is used to irrigate crops, which comes with nitrate to fertilize the soil. Additionally, the leftover flats from the microgreen production are added to the soil to further fertilize it. The farm's dedication to a circular economy was inspiring, demonstrating that a life without waste was not just an ideal but a tangible reality. We ended the day at the farmstand, where In conclusion, the microgreens, greenhouse, fish pond, rabbit production, rainwater harvesting, and zero-waste loop all painted a picture of a harmonious relationship between humanity and nature. As I left the farm, I carried with me not only the flavors of freshly harvested microgreens but also a profound appreciation for the possibilities that a close relationship with nature can offer.

Back to Blog

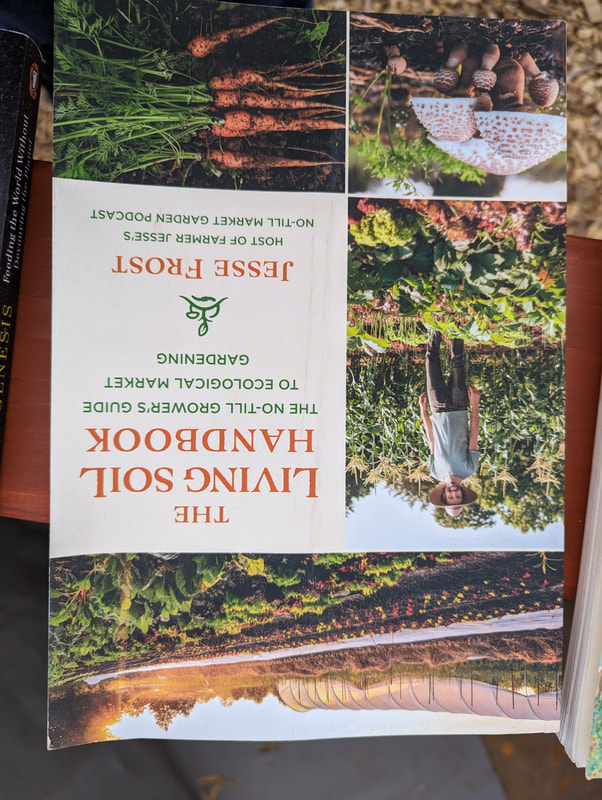

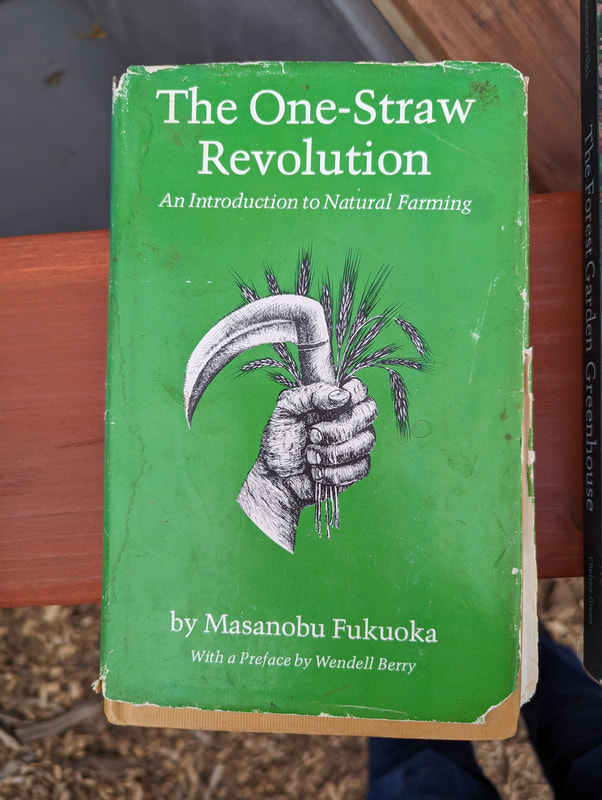

Worm Farm & Soil Workshop @ Colton11/15/2023 Griffin Franklin Fritz started off the workshop by telling us about soil and worm farming and giving us a few recommendations for reading materials about soil including The One Straw Revolution: An Introduction to Natural Farming by Masanobu Fukuoka. We jumped into the action pretty quick splitting into teams to gather materials for sheet-mulching in the new kid's greenhouse (The Bucky Dome" and worm farm building in the hoop house underneath the walkways. Below is the process we followed for building soil for the worm farms.

Below is the process we used for sheet-mulching or making "lasagna beds," as Fritz likes to call them, in the kids' greenhouse.

Back to Blog

Rosemary's Garden Tour & Plant List11/1/2023 by Stephanie Kohnen On November 1, 2023, our permaculture class visited three Flagstaff homes that featured extensive gardens that embrace permaculture principles. The first site we visited was the home of our instructor Rosemary Logan. Rosemary’s house was built in 2012 and is an example of how permaculture ideals can coexist with practical considerations. For example, the entrance to the structure was shifted so that the building could be oriented with its longest side facing south. This allows the greatest absorption of the sun’s warmth during the cooler months. The strategy is part of a passive solar design that increases a building’s energy efficiency. For the structure itself, Apex Block was used. Not only is it more energy efficient than standard building materials, it also qualified for a construction loan. (Straw bales were not eligible for construction loans at that time.) A truth window (see photo below) shows the Apex Block that makes up the interior of the home’s walls. The walls were then covered in plaster. The home features locally sourced materials whenever possible. Wood beams came from local forests. The homeowners also were creative about repurposing items for different uses such as turning a wine barrel into a bathroom sink. (See photo.) Next, Rosemary took us on a tour of her garden. Although the timing of our visit (late Fall) meant the garden had peaked long before, it was evident that harvest was abundant. Both watering and composting systems focus on resource efficiency – conserving water and time. The garden’s watering system is divided by the needs of different plants: native, orchard and annuals. Compost materials are seasonally trenched directly into garden beds for decomposition. Four-inch pipes located at the center of several raised beds are used for vermiculture. Red wiggler worms are replenished each year.  The pipe at the center of this garden bed is used for worm composting (vermiculture). After red wiggler worms are replenished each spring, fruit and veggie scraps can be deposited in the pipe to feed them. Holes have been drilled in the pipe below the soil level so the worms can move freely to access the food and travel around the container. Other tips from Rosemary:

Featured Plants

A garden offers the chance to play and experiment with a variety of plant species. The plants featured in Rosemary’s garden included the following:

Fruit Tree Resource: Trees of Antiquity in upstate New York is a source for well-adapted fruit trees for Flagstaff. OTHER PLANTS On our fieldtrip, we visited two other residential gardens. Below is a list of a few unique plants these gardeners are growing. From Patrick Grant:

From Greg Macallister:

Greg’s kale forest:

Back to Blog

McKenna Bean & Mariessa FowlerGraduate and Junior undergraduate According to the Navajo language, Ch'ishie means "dirty or ashy." This is a perfect name to give a farm that grows food in the desert landscape of the Navajo Nation in northern Arizona. This Friday, the permaculture class had an opportunity to escape the late September chill in Flagstaff and ventured east to Ch'ishie Farms. We arrived at Tyrone's home, which was built with permaculture design in mind, and explored his property, which offered chickens, sheep, hoop houses, and a geodesic dome. The space also serves as a growing space for seed starts, as Tyrone grows about 40,000 seedlings yearly. He showed us his different hoop house models and described the pros and cons of different types of shade cloth and how they facilitate growth throughout harsh conditions. One of his hoop houses uses plastic and shade cloth to insulate the space and allow for a longer growing season, allowing his tomato plants to grow well into November. This hoop house also serves as a windbreak for the rest of the property, as the plastic-reinforced structure does not let wind permeate it. The other hoop house on Tyrone's property incorporates a different shade cloth, allowing outside air to get in through the fabric's holes. This space has fruit trees and premature plant starts and is connected to a geodesic dome. Tyrone is in the process of retrofitting the roof of his home to harvest rainwater to hydrate his at-home garden, which is crucial in this case as everything is hand-watered and this property is off-grid. Finally, we ventured into the garden, where Tyrone and his family built beds made of cinderblocks and other materials. After the tour of his family home, we piled into our vehicles and made the trek down a dirt road to Ch'ishie Farm.

Tyrone's community field is based 11 miles away from his family home. The field runs alongside the Little Colorado River, a lifeline for the Leupp community. Tyrone began this portion of the trip by describing a recent flood that affected this land. It affected infrastructure and some of their equipment was damaged. Every once in a while, the Little Colorado River will flood, submerging the Ch'ishie farm in feet of water. After taking it all in, we began helping Tyrone by picking up and tidying the drip irrigation lines and harvesting corn and squash. We harvested many tubs and wheelbarrows full of corn and squash to be sold at the upcoming Indigenous market held at the Colton Garden, almost filling up the bed of Tyrone's truck! The squash grew massive and it was exciting to weave through the vines for these surprises. Eventually, it was time to head back to Flagstaff and reflect on what we had learned that morning. The dramatic landscape where the desert meets the Little Colorado River mixed with the Lush fields of corn and squash was awe-inspiring and reminded us how resilient agriculture can be. Tyrone is a steward of traditional knowledge and a leader in the local food sovereignty movement. We are so grateful to have had the opportunity to learn from such an influential teacher. Tyrone does a great deal to help his community and during the pandemic, he was able to garner funding to build hoop houses. This encouraged many community members to practice food sovereignty. He mentioned how several other community members utilize the fields during the growing season and grow their intergenerational squash and corn varieties. Many of these farmers also practice dry farming techniques because of the dry and arid environment in the Leupp area. Tyrone also funded a project for solar pumping groundwater for the field and possible future freshwater resources for Leupp. The water was stored on top of a hill and many residents often harvest the water for agricultural or livestock purposes.

Back to Blog

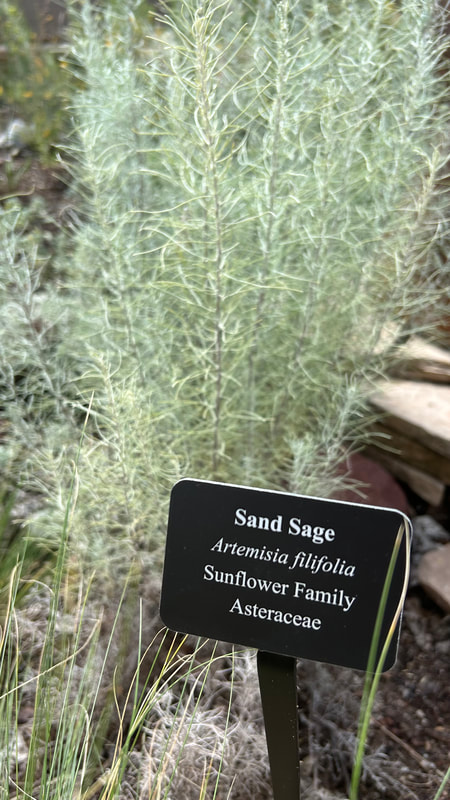

Ben Steller & Mariessa FowlerPermaculture students At the beginning of this field trip, we met with Phyllis Hogan at the Michael Moore Medicinal Garden to talk about medicinal plants and ethnobotany in the Southwest. Phyllis Hogan is a longtime ethnobotanist in the four corners region. In 1976, she created her store in Flagstaff, Arizona, called Winter Sun Trading Co. This local store specializes in the selling of herbal medicinal and local Indigenous art. Then, in 1983, she co-founded the Arizona Ethnobotanical Research Association. This vaulted her into ethnobotanical prominence in the four corners region, and she has been positively contributing to this region ever since. To begin her talk, Phyllis introduced us first to her and her backstory, and then to her methods of honorably and holistically harvesting plants. As she described it, harvesting plants is a privilege and must not be taken lightly. She described how first, one must burn juniper as a method of connecting with plants and connecting with our ancestors. Then she described how we should make a prayer offering to the plant and to the sun. In this prayer offering, she instructed us to tell the plant who we are, and that we should ask for permission to pick it. If it gives us permission, then take responsibility and never overharvest. And if it does not give us permission, she instructed us to never violate that expression from the plant. Only if you go through all of these steps and receive appropriate permission from the plant can you then harvest. For this field trip, we met at the Michael Moore Medicinal Garden. This garden is located on the property of the Museum of Northern Arizona, and it was formerly a parking lot. Now, it is an herbal medicinal garden named after another renowned ethnobotanist of the region, Mr. Michael Moore. This medicinal garden, named after him, is filled to the brim with beautiful medicinal herbs with all sorts of uses. Phyllis showed us examples of some of these herbs from her own collection, among them being the osha root and the yucca root liquid. Both of these have medicinal uses as anti-inflammatory plants. In the garden, we saw lots of sage and various types of medicinal flowers. After touring this garden, we headed up to the Colton Community Garden. The Colton Garden was located right behind the Michael Moore garden and is a communal garden site for the community of Flagstaff. We met with one of the main people who manages the garden, her name is Fitz. She first went over seed saving and how it differs by region. Also how important seeds are because they have genetics and store information. Moreover how you need seeds in order to grow things. For certain seeds, the method of seed saving is different because tomatoes and cucumbers are wet, they require water to germinate. It creates mold which then breaks down the wet layer and you are left with dry seeds. For dry seeds, the process is also different. Community building and sharing is experienced through seed saving. People share their seeds with their neighbors and it usually is for plants that best suit their climate. Then Fitz discussed their favorite vegetable, beans! There are so many varieties of beans especially in this region. Beans grow really well in the Flagstaff region and are beneficial to the soil due to its nitrogen properties. Also they are really good for storing in the winter time and you just need to save a certain percentage for the upcoming growing season. After this demonstration of seed saving and beans overview, we explored the garden. There were a variety of displays for different gardening techniques like keyhole gardening, community composting, sheet mulching, zuni waffle layout, hoop houses, arch trellis for squash, passive solar greenhouses, intercropping, three sisters method, permaculture, and even an indigenous crops garden for a program with indigenous flagstaff students. The keyhole method is best summarized as a compost bin built into the middle of a raised bed. It gives the garden bed the ability to retain moisture, nourish the soil, and improve productivity. The Zuni waffle design is when garden beds are sunken in squares covered with clay or soil walls that keeps water enclosed in these circles. They are efficient in conserving water and improving moisture. The Colton Garden also has a space for children and there is a separate area for children to play. It's behind some willows and connected by a tunnel. There are different books and activities left there for children to interact with while they are there. The kids learn how to plant and harvest. They are currently in the process of creating a geodome for the children to do more planting and growing opportunities. The Colton Garden is very community oriented and actually hosts a lot of events involving the community like workshops and farmer markets. They are open for compost and food scrap collection. But the garden is very inclusive and we can definitely learn from them!

Back to Blog

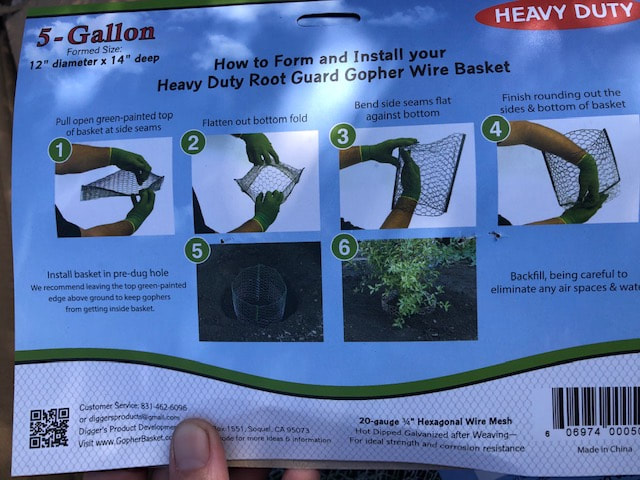

Three Malawians at Colton Garden5/4/2020 Albert Einstein said and we quote, “Never regard study as a duty but as an enviable opportunity to learn to know the liberating influence of beauty in the realm of the spirit for your own personal joy and to the profit of the community to which your later works belong." This was fully manifested when Richard, Shonduri, and I visited Colton garden. It was a normal Friday and as usual in our trio, we decided to visit Colton garden to fulfill the volunteer hours for our class. Colton garden which is Located at 700 feet at the Museum of Northern Arizona (MNA) in Flagstaff, the Colton Community Garden (CCG) is an inspiring space for showcasing high elevation growing strategies and the bio-cultural diversity and heritage of the area. At the heart of the CCG’s mission is to generate, restore and inspire movement towards a more vibrant, resilient and sustainable food system in alignment with MNA’s mission which is to “inspire a sense of love and responsibility for the Colorado Plateau.” We took off at the downtown connection center heading towards Colton garden. Once arriving safely at the garden, we were greeted by Rosemary and Garrod. Rosemary took us to a little tour of the new permaculture food forest section of the garden. Our initial thought was that it this project would be like normal work like we do in Malawi, digging up the soil or mixing the soil with compost and planting trees. It was during the orientation where we learned a different series of challenges with growing at high elevation in an arid landscape- a climate quite different from Malawi. Colton garden faces the usual challenges of growing at high elevation and navigating vermin such as an adjacent prairie dog’s colony and a healthy population of gophers. Despite these challenges the garden has grown exponentially in annual crop production and volunteer participation. In contrast to prairie dogs and gophers, Malawi faces a challenge of termites. These termites attack the roots of the plants. Malawi being a tropical country, has a hot and rainy season from mid-November to April but due to climate change, some areas experience drought whilst other areas experience floods. Due to these challenges, sometimes it is hard to grow crops. A lot of farmers who live in the areas that are affected by drought opt to grow perennial crops like sweet potatoes, and cassava. The leaves of these perennial crops are used as relish. As we started digging the soil, we were surprised to find the chicken wire at the bottom. That was the time we learned about one of the great lessons in the garden. Rosemary explained that there are both gophers and prairie dogs in the area. So, the chicken wire prevents them from attacking the roots of the trees and other annuals. This was the first time we learned of such a simple but innovative way to prevent these animals from attacking the roots of the trees. In this process there are no chemicals applied to the soil, as a result, leaving the soil in its original form permitting microorganisms to breed in large volumes. Other non-organic strategies might involve something like poisoning the gophers and prairie dogs which could be detrimental to the soil and larger ecological health. Other organic ways to control gopher populations include both trapping and inviting predators such as snakes, hawks or owls to the garden. In Malawi, most of the times, the Agriculture Extension Development Officers advice farmers to spray chemicals as one of the ways of dealing with termites. In some cases farmers use ashes who can not afford chemicals use ashes, but this method is less effective because the ashes do not terminate the source of the termites, they only kill those termites that are visible. We continued digging the holes and we managed to dig up to more than 15 holes in readiness for fruit trees which will later be arriving in an order by mail. In each of these holes we placed wire baskets to protect the roots of the trees/shrubs from the gophers. These baskets were called “Root Guard” While these baskets can also be made by hand with leftover wire materials, the funds from permaculture garden fundraiser in December made it possible to purchase these handy baskets. At the end of our work we decided to take a larger tour around the garden. We were amazed by how the land has been effectively been put into use. The demarcations for each crop were marvelous and well thought of. It was obvious that there is so much care that is being put into the land to make sure that it bears the intended fruits. We were astonished by the investment that was done on a small piece of land. The garden is being looked after very well; an indicator to us that people are connecting well with nature. Key reflections that we made after working in the Colton garden included:

Recipe for pumpkin leaves Ingredients 2 lb pumpkin leaves 1big very ripe Tomato 1tsp Salt 6 cups Water 1 cup Groundnut/peanut flour Method Wash the pumpkin leaves and break of the stem and pull of the silk from the pumpkin leaves. Do one leaf at the time and chop them Boil 1cup of water and add salt, Cook the leaves in boiling water for 5-10 mins and add the groundnut flour and the diced tomatoes and simmer for 5-10 mins until tender. Recipe of sweet potato leaves

Ingredients 2 lb Sweet potato leaves 1big very ripe Tomato 1tsp Salt 6 cups Water 1 cup Groundnut/peanut flour ½ Lemon Method Wash the sweet potato leaves and shop them Boil 2cups of water and add salt, diced tomatoes and lemon juice Cook the leaves in boiling water for 5-10mins and add the groundnut flour and simmer for another 5 -10mins until tender.

Back to Blog

Colton Community Garden is located at the Museum of Northern Arizona (www.musnaz.org). The garden is entirely volunteer based and most projects and planting is done in a collective effort. There is a solid group of dedicated volunteers, most notably being Carol Fritzinger. She has been appointed the Garden Manager and has revitalized the Colton Community Garden and made the garden a really special place to be.

I am able to have a compost bin at my house, but not a whole system in the back yard. Because of this, I deliver my compost to the Colton Community Garden. Turns out, Fritz needed help with converting three more garden beds into lasagna beds. I was semi-familiar with lasagna beds, but I had never built one before. The awesome aspect about lasagna beds is that they are essentially ready-made compost beds that can be directly seeded and transplanted in. There is no strict formula for constructing a lasagna bed, but in general, “brown” and “green” materials are layered, like a lasagna casserole, over a heavy layer of organic material such as cardboard and newspaper. Brown materials are high in carbon and can consist of dried leaves, mulch, and straw or hay. Green materials are high in nitrogen and can include fresh yard and kitchen waste as well as manure. You ~can~ get super technical about it, but plants LOVE carbon and nitrogen, so its no biggie if you don't follow an exact science. The process for building these specific lasagna beds went as follows: I dug out the current beds, carefully saving the existing soil. Then, I removed the plastic from the cardboard box and placed them on the bottom of the bed, followed by enough water to thoroughly soak the cardboard. A layer of soil was added. I then put a few containers of raw compost and followed with another layer of soil. Next, I dumped coffee grounds from Starbucks in the bed, also followed by soil. The next few layers of brown and green material consisted of leaves and animal manure, separated by layers of soil. Once the bed was full and topped off with soil, a burlap covering was placed over the exposed soils to prevent erosion and the loss of soil. Working at the Colton Community Garden and helping Fritz with installing lasagna beds has so much potential impact on the garden. Soil made in lasagna beds is packed with carbon and nitrogen, which plants thrive from. Produce grown in these beds will have higher yields, grow stronger, and will serve more people than produce grown in regular garden soil. The impact the community gardens and composting can have in the world is insurmountable. We can heal social and ecological connections by composting and gardening as a community. Happy Gardening!!! <3 -Pamela Hobbs-Laventall |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed